Tales from the Qissa Khwani Bazaar

Written by Joobin Bekhrad on July 24, 2012.

ZALAN KHAN’S QUEST TO BATTLE STEREOTYPES ABOUT A TUMULTUOUS AND WIDELY MISUNDERSTOOD REGION

There’s no doubt that the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a region located between Afghanistan and Pakistan, has seen its share of violence, lawlessness, war, and turmoil. However, there’s so much more to this vast and diverse land that is home to myriad peoples and traditions, and its unfortunate that people both in the region and in the West are only exposed to the darker side of the story.

Luckily for us, Zalan Khan and the writers at Qissa Khwani, in the ancient tradition of their storytelling ancestors, are providing alternative perspectives to the ones channeled through the media, in the hope of changing the way the region is perceived throughout the world. I had the chance to speak to Zalan (a Peshawari native) about this wonderful initiative, as well as his thoughts on the FATA region itself and the endangered art of storytelling therein.

What is Qissa Khwani, and why did you establish the site?

The name, Qissa Khwani, is a reference to the old Qissa Kwhani Bazaar (Lit. ‘Storytellers’ Market) in the city of Peshawar. Historically, the marketplace was a stopping point for caravans travelling eastwards to Delhi, or westwards and northwards as far as Baghdad, and even the golden road to Samarkand! The biggest ethnic group in this area are Pashtuns, but it is also home to other ethnic groups, including Dari (a Persian variant) speaking Tajiks, Hazaras, Hindko speakers and the Baloch. The traders would have probably in between business exchanges over carpets, spices, and furs, sat down in the local tea houses and swapped stories of local areas and faraway lands. This tradition of storytelling – the telling of a local ‘narrative’ – is what really inspired the creation of the website. There were other influences as well, as for someone with close ties to the region, I had yet to see a newspaper or website where I could find out what was really happening in the region. The national and foreign newspapers wrote in broad brushes, missing out on cricual bits of context. Finally, one day a year back I wrote an article entitled Pashtuns: Chowkidars or Noble Savages? and finally decided to set up Qissa Khwani.

You once mentioned to me that the Federally Administered Tribal Areas are negatively portrayed in the Western media, and that you are unhappy about this. How do you view the region, and what role do you see yourself playing in changing the way people perceive it?

I do not neccesarrily see it being something exclusive to the Western media; the national Pakistani media has been as equally complicit. Furthermore, I don’t see the issue being specific to Pakistan’s FATA alone, but rather to the entire region stretching from Herat in Afghanistan, to Attock in Pakistan, to as far north as Chitral, right down to the Baloch areas of Pakistan. My issue is not with necessarily what is reported (although that is also an issue), as much as the fact that we usually only hear one side of the story. As Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie so astutely remarked, ‘the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story’.

The region is experiencing unprecedented turmoil. Beyond the tens of thousands that have died, schools have been destroyed, and hundreds of thousands have been displaced. There has been a generation brought up to live amidst instability, and surrounded by money, weapons, radicalisation, and drugs. To give you some examples of the insecurity, in the first three months of 2009, there were 200 kidnappings for ransom in Peshawar, while according to another source in the city of Quetta, over 800 Hazaras were killed in 24 incidents of mass-murder, in addition to there being 131 targeted ambushes since 2001.

Thus, articles or reports to do with people who live in the area are often written by outsiders, and are simplified into stereotypes (although some are benign) about terrorists, backward war-like savages, graveyards for empires, and long-bearded lawlessness. That isn’t the case, however. The locals are people who live, love, bleed, and die like everyone else. Their lives and stories are as worthy of attention as those of anyone else’s, and are just as interesting, if not more.

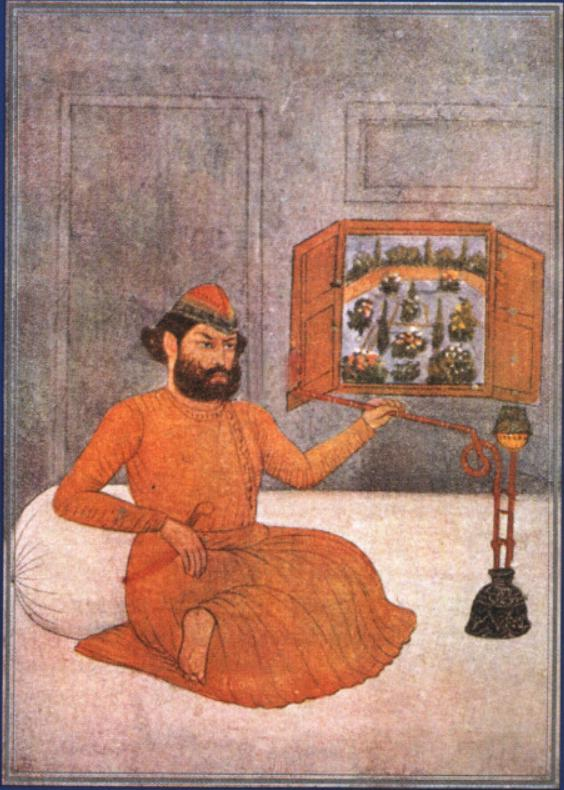

A Chaiwalla

A Chaiwalla

The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Your site describes itself as a storyteller’s bazaar. What is the current state of storytelling in countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan? Are traditional storytellers still relevant, or are they fast succumbing to the changes brought about by modernity?

Storytelling is always relevant. It reminds us of what the world was like, and where we are today. More importantly, stories remind us to hope and dream for a better future.

Unfortunately, storytelling faces several challenges in the region. For one, storytelling depends on the presence of curious audiences, and people willing to spend time to listen to stories. As well, there is a lack of money to spend on literacy, and one cannot freely express oneself without fear of reprisal. In the case of the latter, most of the books about the region are written by outsiders, and at the same time, there are local bookshops unable to turn a profit and are closing down as a result. While that might sound negative, I would argue that there are many writers, storytellers, and readers out there; all they need is the right platform.

In addition to the material on Qissa Khwani, what books would you recommend as a primer to further understanding the region (i.e. the F.A.T.A.), and going beyond the headlines? I’ve just recently read a book by Jamil Ahmad (who once lived in the region), called The Wandering Falcon, which, although it was a wonderful story, did not do much to promote the positive aspects of the region.

The Wandering Falcon is an excellent novel, and it serves its purpose as a story. If you enjoyed it, I would also recommend The Pathans by Ghani Khan, which is available for free online. Both both books talk about a time that has passed two generations back.

How do you view the future of the Qissa Khwani website?

In broad terms, it will hopefully become a website which will feature a variety of different writers, writing on everything from politics, history, and culture, to travel and fiction. And perhaps – just perhaps – one of our writers will one day tell the world a story that will change how others perceive the region.

Visit the Qissa Khwani website at www.qissa-khwani.com.

About Joobin Bekhrad:

Joobin Bekhrad Joobin is the Founder and Editor of REORIENT, and the Co-Founder

Written by Joobin Bekhrad on July 24, 2012.

ZALAN KHAN’S QUEST TO BATTLE STEREOTYPES ABOUT A TUMULTUOUS AND WIDELY MISUNDERSTOOD REGION

There’s no doubt that the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a region located between Afghanistan and Pakistan, has seen its share of violence, lawlessness, war, and turmoil. However, there’s so much more to this vast and diverse land that is home to myriad peoples and traditions, and its unfortunate that people both in the region and in the West are only exposed to the darker side of the story.

Luckily for us, Zalan Khan and the writers at Qissa Khwani, in the ancient tradition of their storytelling ancestors, are providing alternative perspectives to the ones channeled through the media, in the hope of changing the way the region is perceived throughout the world. I had the chance to speak to Zalan (a Peshawari native) about this wonderful initiative, as well as his thoughts on the FATA region itself and the endangered art of storytelling therein.

What is Qissa Khwani, and why did you establish the site?

The name, Qissa Khwani, is a reference to the old Qissa Kwhani Bazaar (Lit. ‘Storytellers’ Market) in the city of Peshawar. Historically, the marketplace was a stopping point for caravans travelling eastwards to Delhi, or westwards and northwards as far as Baghdad, and even the golden road to Samarkand! The biggest ethnic group in this area are Pashtuns, but it is also home to other ethnic groups, including Dari (a Persian variant) speaking Tajiks, Hazaras, Hindko speakers and the Baloch. The traders would have probably in between business exchanges over carpets, spices, and furs, sat down in the local tea houses and swapped stories of local areas and faraway lands. This tradition of storytelling – the telling of a local ‘narrative’ – is what really inspired the creation of the website. There were other influences as well, as for someone with close ties to the region, I had yet to see a newspaper or website where I could find out what was really happening in the region. The national and foreign newspapers wrote in broad brushes, missing out on cricual bits of context. Finally, one day a year back I wrote an article entitled Pashtuns: Chowkidars or Noble Savages? and finally decided to set up Qissa Khwani.

You once mentioned to me that the Federally Administered Tribal Areas are negatively portrayed in the Western media, and that you are unhappy about this. How do you view the region, and what role do you see yourself playing in changing the way people perceive it?

I do not neccesarrily see it being something exclusive to the Western media; the national Pakistani media has been as equally complicit. Furthermore, I don’t see the issue being specific to Pakistan’s FATA alone, but rather to the entire region stretching from Herat in Afghanistan, to Attock in Pakistan, to as far north as Chitral, right down to the Baloch areas of Pakistan. My issue is not with necessarily what is reported (although that is also an issue), as much as the fact that we usually only hear one side of the story. As Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie so astutely remarked, ‘the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story’.

The region is experiencing unprecedented turmoil. Beyond the tens of thousands that have died, schools have been destroyed, and hundreds of thousands have been displaced. There has been a generation brought up to live amidst instability, and surrounded by money, weapons, radicalisation, and drugs. To give you some examples of the insecurity, in the first three months of 2009, there were 200 kidnappings for ransom in Peshawar, while according to another source in the city of Quetta, over 800 Hazaras were killed in 24 incidents of mass-murder, in addition to there being 131 targeted ambushes since 2001.

Thus, articles or reports to do with people who live in the area are often written by outsiders, and are simplified into stereotypes (although some are benign) about terrorists, backward war-like savages, graveyards for empires, and long-bearded lawlessness. That isn’t the case, however. The locals are people who live, love, bleed, and die like everyone else. Their lives and stories are as worthy of attention as those of anyone else’s, and are just as interesting, if not more.

A Chaiwalla

A Chaiwalla

The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Your site describes itself as a storyteller’s bazaar. What is the current state of storytelling in countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan? Are traditional storytellers still relevant, or are they fast succumbing to the changes brought about by modernity?

Storytelling is always relevant. It reminds us of what the world was like, and where we are today. More importantly, stories remind us to hope and dream for a better future.

Unfortunately, storytelling faces several challenges in the region. For one, storytelling depends on the presence of curious audiences, and people willing to spend time to listen to stories. As well, there is a lack of money to spend on literacy, and one cannot freely express oneself without fear of reprisal. In the case of the latter, most of the books about the region are written by outsiders, and at the same time, there are local bookshops unable to turn a profit and are closing down as a result. While that might sound negative, I would argue that there are many writers, storytellers, and readers out there; all they need is the right platform.

In addition to the material on Qissa Khwani, what books would you recommend as a primer to further understanding the region (i.e. the F.A.T.A.), and going beyond the headlines? I’ve just recently read a book by Jamil Ahmad (who once lived in the region), called The Wandering Falcon, which, although it was a wonderful story, did not do much to promote the positive aspects of the region.

The Wandering Falcon is an excellent novel, and it serves its purpose as a story. If you enjoyed it, I would also recommend The Pathans by Ghani Khan, which is available for free online. Both both books talk about a time that has passed two generations back.

How do you view the future of the Qissa Khwani website?

In broad terms, it will hopefully become a website which will feature a variety of different writers, writing on everything from politics, history, and culture, to travel and fiction. And perhaps – just perhaps – one of our writers will one day tell the world a story that will change how others perceive the region.

Visit the Qissa Khwani website at www.qissa-khwani.com.

About Joobin Bekhrad:

Joobin Bekhrad Joobin is the Founder and Editor of REORIENT, and the Co-Founder